Jean-Jacques Rousseau was one of the great French philosophes, whose influence permeates nearly every field of the humanities and social sciences.

Below is an excerpt from a biography of Jean-Jacques Rousseau included with our books.

| Title | Published |

|---|---|

| Discourse on the Arts and Sciences | 1750 |

| The Social Contract | 1762 |

Jean Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva on June 28, 1712 and his mother died nine days after his birth. Rousseau did not go to a school to receive a formal education. His father Isaac Rousseau was a watchmaker who raised and educated Rousseau until the age of ten. Little Rousseau loved reading classical authors such as Plutarch of the Roman republic.

Rousseau left Geneva to Turin at the age of sixteen under the influence by Baronne de Warens. Rousseau spent some time working as a domestic servant and converted to Roman Catholicism in April 1728 in Turin.

In general Rousseau’s formal education was very limited during his teenage. He was somewhat confused during the childhood. At age 13, Rousseau was apprenticed first to a notary and then to an engraver who beat him. At 15, he ran away from Geneva on 14 March 1728.

During his early age, Rousseau learned the real world through working as a servant, secretary, and tutor, wandering at Piedmont and Savoy in Italy and France. He briefly attended a seminary with the idea of becoming a priest. De Warens also helped him get started in a profession and arranged formal music lessons for him.

Rousseau had been an average student, but during his 20s, he applied himself in earnest to the study of philosophy, mathematics, and music.

At the age of 25, Rousseau received an inheritance from his mother and he used a portion of it to repay De Warens for her financial support of him.

At 27, he found a job to work as a tutor in Lyon, France.

In 1742, Rousseau moved to Paris in order to present the Académie des Sciences with a new system of numbered musical notation. However, his system was rejected though Académie des Sciences praised his mastery of the subject.

From 1743 to 1744, Rousseau had an honorable post as a secretary to the Comte de Montaigue, the French ambassador to Venice. The Venice experience built his lifelong love for Italian music and opera.

After 11 months of Venice tenure track, Rousseau quitted due to a profound distrust of government bureaucracy.

Returning to Paris, Rousseau befriended and became the lover of Thérèse Levasseur. In his letter to Madame de Francueil in 1751, he said that he wasn’t rich enough to raise his children. However, in book of the Confessions, he also said that “I trembled at the thought of entrusting them to a family ill brought up, to be still worse educated. The risk of the education of the foundling hospital was much less.”

In 1761, Rousseau was popular as a theorist of education and child-rearing. However, his abandonment of his children was used by Voltaire and Edmund Burke as the basis for ad hominem attacks.

While in Paris, Rousseau became a close friend of French philosopher Diderot in 1749 and contributed numerous articles to Diderot and D’Alembert’s great Encyclopédie.

Rousseau’s ideas were the result of conversation with Diderot. In 1749 for the entire year, Rousseau was paying daily visits to see Diderot who were in the fortress of Vincennes for opinions in his “Lettre sur les aveugles” that he hinted at materialism with a belief in atoms and natural selection.

Rousseau’s Discourse on the Arts and Sciences in 1750 was awarded the first prize for an essay competition sponsored by the Académie de Dijon to be published in the Mercure de France on the theme of whether the development of the arts and sciences had been morally beneficial. In this important essay, he had a revelation that the arts and sciences were responsible for the moral degeneration of mankind who were basically good by nature. This essay gained him significant fame.

In 1752, Rousseau wrote the words and music of his opera Le Devin du Village for King Louis XV. The king was so pleased by the work so that he offered Rousseau a lifelong pension. However, Rousseau turned down the great honor and several other advantageous offers for his friend in the fortress of Vincennes.

Rousseau reconverted to Calvinism and regained his official Genevan citizenship after returning to Geneva in 1754.

In 1755, Rousseau completed his second major work, the Discourse on Inequality, which elaborated on the arguments of the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences.

Rousseau was inspired to write his epistolary novel Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse due to a romantic attachment with the 25-year-old Sophie d’Houdetot. The novel was published in 1761 to immense success.

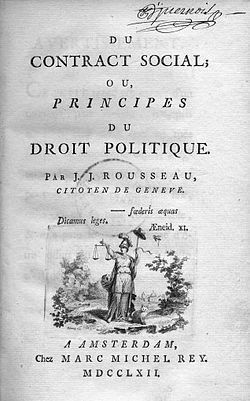

In April 1762, Rousseau published Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique (Of the Social Contract, Principles of Political Right). The Social Contract implied that the concept of a Christian Republic was paradoxical since Christianity taught submission rather than participation in public affairs. Even his friend Antoine-Jacques Roustan felt impelled to write a polite rebuttal of the book.

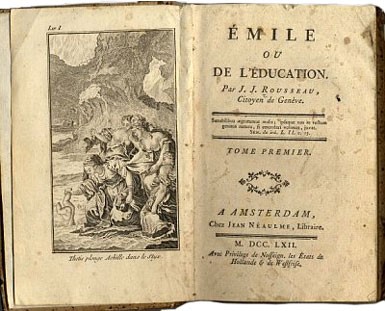

Rousseau published Emile (On Education) in May 1762. The section The Profession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar in Émile was a defense of religious indifferentism. This caused Rousseau and his books to be banned from France and Geneva. Scottish philosopher David Hume supported him by saying Rousseau “has not had the precaution to throw any veil over his sentiments; and, as he scorns to dissemble his contempt for established opinions, he could not wonder that all the zealots were in arms against him. The liberty of the press is not so secured in any country… as not to render such an open attack on popular prejudice somewhat dangerous.”

After publishing Emile, Rousseau was forced to flee arrest due to offending the authority. He made his way to Môtier of Swiss. While in Môtiers, Rousseau wrote Projet de Constitution pour la Corse in 1765.

In September 1765, Rousseau took refuge in Great Britain with Hume, who found lodgings for him at a friend’s country estate in Wootton in Staffordshire.

Rousseau returned to Paris in 1767 under a false name. In 1768, he went through a marriage of sorts to Thérèse (marriages between Catholics and Protestants were illegal during their time).

In 1770, they were allowed to return to Paris. However, as a condition of his return, he was not allowed to publish any books.

In 1782, The Confessions was only partially published four years after his death. All his subsequent works were to appear posthumously.

In 1772, Rousseau wrote his last major political work, the Considerations on the Government of Poland, due to an invitation to write a new constitution for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In 1776, he completed Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques and the work on the Reveries of the Solitary Walker.

Rousseau’s final years were largely spent in home in order to support himself. He returned to copying music, spending his leisure time in the study of botany. On July 2, 1778, Rousseau suffered a hemorrhage while walking on the estate of the marquis René Louis de Girardin at Ermenonville near Paris. He died on the day at the age of 66.

Rousseau was initially buried at Ermenonville on the Ile des Peupliers. Sixteen years after his death, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris in 1794 along with those of his contemporary, including Voltaire.

In 1834, the Geneva government built a statue in Rousseau’s honor on Lake Geneva to claim him as their proud son.